In May, the government announced a salary increase of more than 13%, effective December, for the 1.6 million civil servants. The Congress of Unions of Employees in the Public and Civil Services (Cuepacs) did not have to use threats or go on strike to achieve this.

Today, political parties court the civil service vote bank – about 91% of whom are Malays – to win elections. So, it makes government-union negotiations so much easier.

However, in the early years of the trade union movement, pioneer unionists had to fight the colonial government for every small advance.

Not many are aware that there was a time when about 65,000 local government workers were daily-rated and there were no pensions.

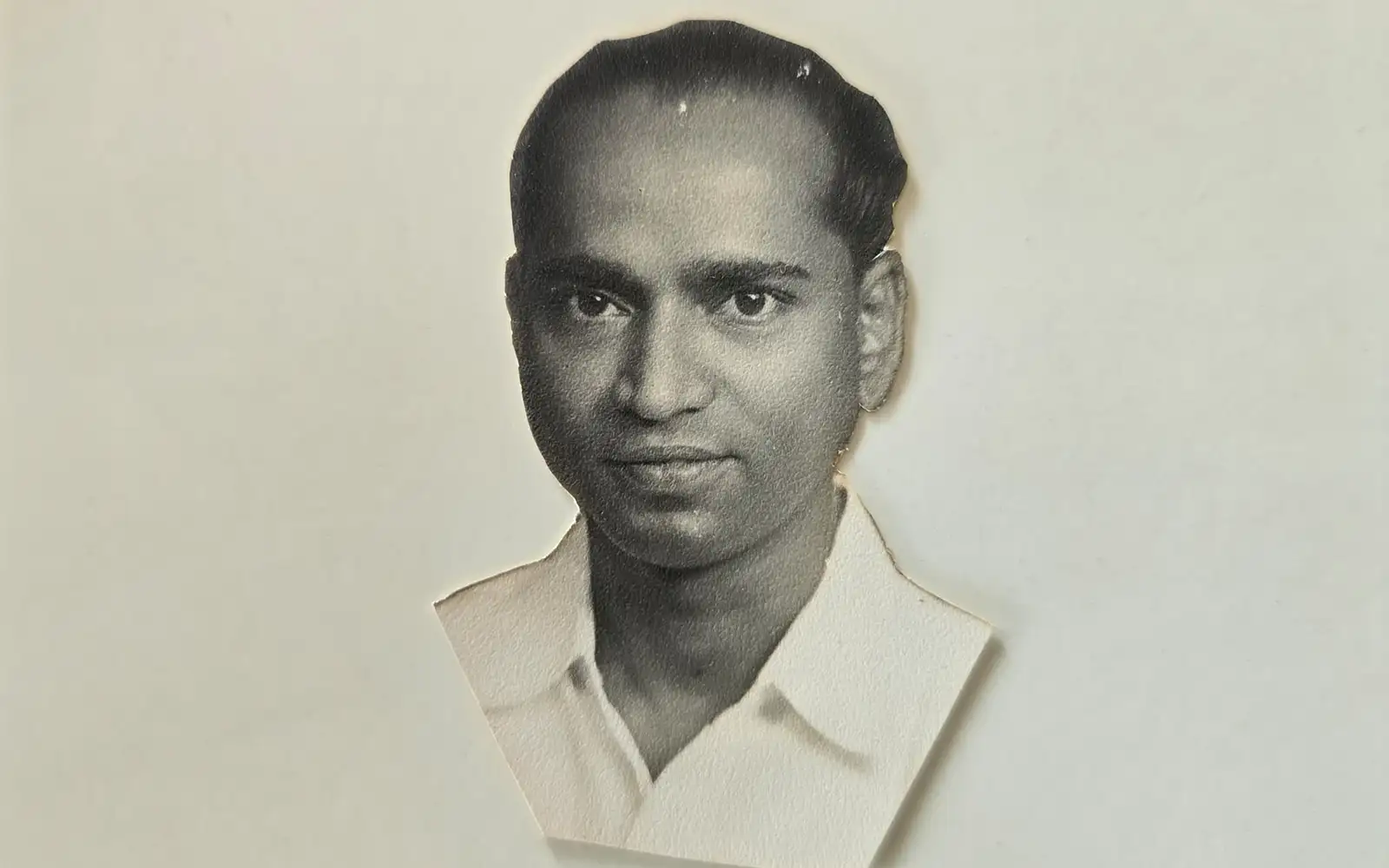

Few, if any, are aware that they owe a huge debt to early trade unionists such as MP Rajagopal, who championed the betterment of workers, particularly in the railways and government service.

Rajagopal rallied railway workers and led the first post-World War II strike in Malayan history, according to a citation at the inauguration of a library in his honour within the MTUC premises in the 1980s.

Rajagopal, who has been described as a “folk hero”, helped form the All-Malaya Railway Workers Union, becoming its first president after the strike.

In 1947, at the age of 28, Rajagopal was appointed a member of the Malayan Union Advisory Council, which, a year later was renamed the Federal Legislative Council, the precursor of today’s Parliament. He was at that time the youngest man ever to be appointed to a government legislative body.

He was also the chairman of the Joint Council of Government Daily-Rated Workers Trade Unions and sat on six government committees.

Rajagopal was born in Pasir Mas, Kelantan, in 1922 to railway worker Muthusamy Parthasarathy, according to his youngest son Siva, a retired teacher.

Rajagopal dropped out after Standard Six and worked odd jobs to help support the family. Later, he joined the Malayan Railways as a fitter and, over time, became workshop inspector and planner in the chief mechanical engineer’s department.

“In 1941, my father married Latchmi Appiah and they had 10 children, six boys and four girls. He was a disciplinarian and always emphasised the importance of education,” said eldest son Veera Kumar, 77, who was in government service as a dental technologist for 34 years.

Veera Kumar said his father was out of the house most of the time, attending to union matters.

Siva chipped in: “Having lived in poverty and experienced the tough life of ordinary workers, my father had a natural inclination to fight for workers’ rights and to help the poor.

“My mother told us he would even buy groceries for some of the poorer families.”

After the Japanese surrendered and the British returned to rule Malaya, they continued to pay railway workers and others pre-World War II wages.

In 1947, Rajagopal was earning $3.20 a day plus cost-of-living allowances amounting to another dollar. Many workers were earning less than $2.50 a day despite the cost of living going up manifold after the war.

That set the stage for conflicts between the British Military Administration (BMA) and Rajagopal who led railway workers to stage a strike, forcing train services to a halt for about a month. Finally, the BMA gave in.

Subsequently, the British appointed him a member of the Malayan Union Advisory Council.

The Straits Times of April 13, 1947 had this to say about his appointment: “It is the first time in history that a daily-paid worker takes his seat in the legislature. He will sit beside men who are on the highest government salary or have big private incomes.”

When the Malayan Union Advisory Council was disbanded, following protests against the Malayan Union proposal, and the Federal Legislative Council (FLC) formed, Rajagopal was appointed to it.

In February 1950, his motion to establish a provident fund for daily-rated workers was approved by the FLC.

The following year, he successfully pressed for better pay and increased cost of living allowances. That December, the government paid salary and cost of living allowance arrears totalling $1.25 million to daily paid government workers.

In June 1953, he led a sit-down strike to get holidays for the 65,000 daily-rated government employees. In January 1956, he fought for the lowest paid government worker to be paid $4 a day, up from the $2.28 cents they were earning.

Also in the FLC then, was PP Narayanan, then the president of the Negeri Sembilan Estate Workers Union.

Narayanan, Rajagopal and others, with the backing of the British authorities, initiated a conference of Malayan trade union delegates on Feb 27-28, 1949 with the aim of forming an umbrella body. Rajagopal was the chairman of the conference.

A total of 160 delegates from 83 unions attended. Public leaders such as Onn Jaafar, the founder-president of Umno, Tan Cheng Lock, the founder-president of MCA, and lawyer R Ramani, who went on to become Malaya’s first UN representative and president of the UN Security Council, gave speeches.

At the second conference of Malayan trade union delegates on March 25-26 the following year – attended by representatives of 111 unions and opened by Onn Jaafar – the Malayan Trade Union Council was formed.

It trumpeted a new beginning for the trade union movement, with Narayanan as president, Che Rahmah Mohd Salleh as vice-president, XE Nathan as secretary and Rajagopal as financial secretary.

Although slight in build and small in size, Rajagopal packed a wallop when it came to labour rights, earning the nickname “labour’s watchdog”. He died in 1967 from poor health.

Siva said: “He pushed for the establishment of a provident fund in 1950. The following year the Employees Provident Fund was established.

“If today workers enjoy better pay and perks, it is in no small measure thanks to the sacrifices and farsightedness of pioneers like Dr Narayanan and my father.”

Desain Rumah Kabin

Rumah Kabin Kontena

Harga Rumah Kabin

Kos Rumah Kontena

Rumah Kabin 2 Tingkat

Rumah Kabin Panas

Rumah Kabin Murah

Sewa Rumah Kabin

Heavy Duty Cabin

Light Duty Cabin

Source

![Perjuangan Ikhlas Aiman Ameer, Hero Remaja 2023 [Isu Digital Februari 2024] Perjuangan Ikhlas Aiman Ameer, Hero Remaja 2023 [Isu Digital Februari 2024]](https://cdn.remaja.my/2024/01/Aiman-Ameer_Cover.png)